#Ireland

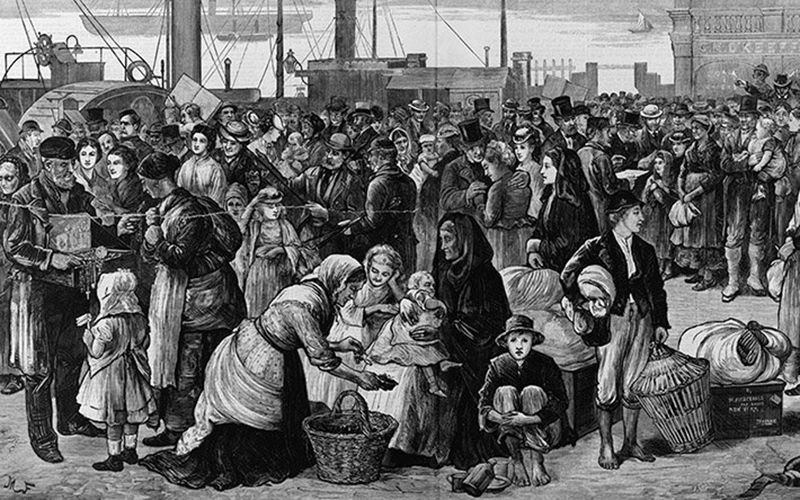

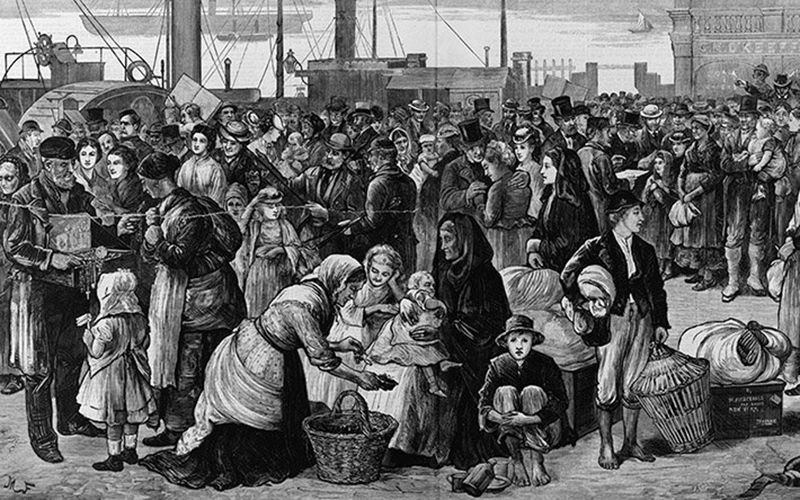

Grosse Île, in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence in Quebec, Canada, acted as a quarantine station for Irish people fleeing the Great Hunger between 1845 and 1849. It is believed that over 3,000 Irish people died on the island and over 5,000 are buried in the cemetery there. On May 31, 1847, 40 ships lay off Grosse Île with 12,500 passengers packed as human ballast.

Memorial erected in 1909 in commemoration of the death of Irish immigrants of 1849 (see photo)

On the memorial is “Children of the Gael died in their thousands on this island having fled from the laws of foreign tyrants and an artificial famine in the years 1847-48. God’s blessing on them. Let this monument be a token and honor from the Gaels of America. God Save Ireland”

It was stated that there was nothing more terrible than the sheds. Most of the patients were attacked with dysentery and the smell was dreadful, as there was no ventilation.

“Frs Moylan and O'Reilly saw the emigrants in the sheds lying on the bare boards and ground for whole nights and days without either bed or bedding. Two, and sometimes three, were in a berth. No distinction was made as to sex, age or nature of illness. Food was insufficient and the bread not baked. Patients were supplied three times a day with tea, gruel or broth. How any of them ever recovered is a wonder. Fr O'Reilly visited two ships, the Avon and the Triton. The former lost 136 passengers on the voyage and latter 93. All these were thrown overboard and buried in the Atlantic. He administered the last rites to over 200 sick on board these ships. Fr Moylan's description of the condition of the holds of these vessels is simply most revolting and horrible.

As for the dead, who were not buried at sea, it has been already seen how they were taken from the pest ships and corded like firewood on the beach to await burial. In many instances the corpses were carried out of the foul smelling holds or they were dragged with boat-hooks out of them by sailors and others who had to be paid a sovereign for each.

A word more as to the removal of the corpses from the vessels. They were brought from the hold, where they darkness was, as it were, rendered more visible by the miserable untrimmed oil lamp that showed light in some places sufficient to distinguish a form, but not a face. It was more by touch than by sight that the passengers knew each other. First came the touch and then the question, who is it? Even in the bunks many a loved one asked the same question to one by his or her side, for in the darkness that reigned their eyesight was failing them.

The priest, leaving daylight and sunlight behind, as each step from deck led him down the narrow ladder into the hold of the vessels of those days, as wanting in ventilation as the Black Hole of Calcutta, had to make himself known and your poor Irish emigrant with the love and reverence he had for his clergy, who stuck to him through thick and thin, endeavoured to raise himself and warmly greet him with the little strength that remained.”

The following reminded me of the Killing fields I visited in Cambodia

“Another death announced, orders were given by the captain for the removal of the body. Kind hands in many cases attended to this. In other cases, as we have seen, it was left to strangers. Up the little narrow ladder to the deck, were the corpses borne in the same condition in which they had died, victims among other things of filth, uncleanliness and bed sores and with hardly any clothing on them. There was no pretence of decency or the slightest humanity shown.

On deck a rope was placed around the emaciated form of the Irish peasant, father, mother, wife and husband, sister and brother. The rope was hoisted and with their heads and naked limbs dangling for a moment in mid-air, with the wealth of hair of the Irish maiden, or young Irish matron, or the silvered locks of the poor old Irish grandmother floating in the breeze, they were finally lowered over the ship's side into the boats, rowed to the island and left on the rocks until such time as they were coffined. Well might His Grace the Archbishop of Quebec, in his letter to the Bishops of Ireland, say that the details he received of the scenes of horror and desolation at the island almost staggered belief and baffled description.

There was no delay in burying the dead. The spot selected for their last resting place was a lonely one at the western end of the island at about 10 acres from the landing. At first the graves were not dug a sufficient depth. The rough coffins were piled one over the other and the earth covering the upper row, in some instances, was not more than a foot deep and generally speaking about a foot and a half. The cemetery was about 6 acres in extent. Later huge trenches were dug in it about 5 or 6 deep and in these the bodies were laid often uncoffined. Six men were kept constantly employed at this work.

Béchard, in his history of the island, adds a new horror to the ghoulish scene. He states that an army of rats, which had come ashore from the fever ships, invaded the field of death, took possession of it and pierced it with innumerable holes to get at and gnaw the bodies buried in the shallow graves until hundreds of loads of earth had to be carted and placed upon them.”

And as if this terrible almost incredible state of affairs were not sufficient, outside the hospitals no order was observed. The very police, who were appointed to maintain order, were the first to set an example of drunkenness and immorality. Is it to be wondered at then that great difficulty was experienced in retaining honest nurses or attendants who had a reputation to sustain? On those days of the week, when the opportunity of leaving the island was offered by the arrival of the steamer from Quebec, a great number of servants insisted upon their discharge but such applications were firmly refused, unless the applicants could produce a substitute. It is hardly necessary to say that many, so retained against their will, neglected their duty to the sick and sought by every means to provoke their dismissal.

Nurses were obliged to occupy a bed in the midst of the sick and had no private apartment where they could change their clothing. Their food was the same as was given to the emigrant and had to be taken in haste amid the effluvia of the sheds and in this way they were frequently infected with fever. When they fell sick they were left to themselves.

The report of these melancholy events magnified by rumour, circulated in Quebec to such an extend that none were willing to expose themselves to a fate which seemed to wait on those who had the care of the sick. What happened? The door of the common jail was thrown open and its loathsome inmates were sent to Grosse Isle to nurse the pure, helpless Irish youth.

IrishCentral.com

On This Day: 40 Irish Famine ships anchored at Grosse Île quarantine station in 1847

On May 31, 1847, 40 ships lay off Grosse Île in Quebec, Canada packed with some 12,500 people fleeing the Irish Famine.

The Grosse Ile Tragedy

The Grosse Ile Tragedy: Irish famine emigrants at Grosse Ile in Canada